- Posted on June 7th, 2024

Commodity, archive, knowledge-holder: the global importance of water

Our Cornwall based, ocean-loving Sustainability Coordinator Lukas Fraser writes about threats to the planet’s oceans, their vital importance, and creative and cultural responses that explore our relationship with water, from pollution, scarcity, and salinity to spirituality.

After spending most of my life with minimal interaction with the ocean, I recently moved to a beach town in Cornwall. Almost everyone’s spare time here is spent in and around their local beach, swimming, fishing, surfing. The ocean is embedded in the fabric of these towns and their culture: local businesses and creatives will choose names inspired by their surrounding marine environment, in a way that’s not mimicked in landlocked towns.

While swimming is an everyday practice, it’s increasingly common for beach visitors to check the local sewage warnings before considering entering the water. An app with map data from regular beach monitoring, published by Surfers Against Sewage, marks beaches around the UK where it’s safe to swim and where it’s unsafe due to local sewage pollution. Exposure to raw sewage, which carries e-coli and heavy metals, can have various negative health effects. This map is now something that almost everyone I know locally has on their phone.

This daily adaptation showcases the ways humans are impacted by the massive increase in raw sewage inputs into UK waterways in recent years. Sewage input also contributes to algal blooms, which starve habitats of oxygen and cause the deaths of marine and freshwater species. These algal blooms also impact the pH of the ocean, putting further pressure on the issue of ocean acidification; one of the nine planetary boundaries.

This is just one small way in which the current context of our waterways impacts myself and my home. In a more global context, the impacts are far more severe and only predicted to cause further devastation. Rising sea levels as a result of glacial melt and thermal expansion of seawater contribute to freshwater intrusion and salinisation, coastal flooding, infiltration of vital groundwater by saline water, and the increased intensity of threats such as storm surges. Glacial melt also has localised impacts, including flooding, crop failure, and increased stress on water supplies. It’s now almost impossible to find water without microplastics in, and they continue to pass through the Earth’s shared water cycle. A milieu of chemical materials are also discharged into our water systems on a constant basis, from antibiotics, to pesticides, to crude oil. These are now a key component of our global water cycle, but it has disproportionate impacts.

Global power flows

This current context is something that we truly share as a planetary ecosystem. Thinking about our relationship – our closeness – with water, Astrida Neimanis, a cultural theorist exploring hydrofeminism, puts it best:

“Just as the deep oceans harbor particulate records of former geological eras, water retains our more anthropomorphic secrets, even when we would rather forget. Our distant and more immediate pasts are returned to us in both trickles and floods.”

As living organisms, we all contain and desperately rely on water. Looking back to the primordial soup, our origin as terrestrial beings, we have all come from water. Each of us carries inside us a wetland ecosystem of our own, which witnesses and feels a microcosm of anthropogenic impacts passing through us in the water we consume: microplastics, forever chemicals, pollution. In this way, we are never separated from the ecosystems we pollute. The water we consume, and hold within ourselves fleetingly, has been everywhere. It’s the same water that our ancestors used. The same water that once flooded the Sahara.

One of the key ways in which one can understand the current risks to our global water systems is by thinking about the balance between freshwater and saltwater. Both of these types of water are integral to a lot of the systems that keep the Earth’s ecosystems thriving. Maintaining the distinction between them (with the exception of brackish waters e.g. in estuaries, where some ecosystems rely on a low level of salinity) is important. Saltwater intrusion into freshwater poses a significant threat to irrigation systems and drinking water provisioning. It also threatens ecosystems, shifting the location of wetlands and killing trees in forests. On the other side, glacier melt e.g. from the Greenland Ice Sheet into the Atlantic ocean decreases the salinity of the seawater, causing thermohaline currents such as the Gulf Stream to collapse, thereby preventing the distribution of warm water across the ocean and causing temperature drops in Western Europe and North America and disruption of rainfall in West Africa and South America.

As strains like these are put on our water supplies and scarcities become an increasing threat, water inequality and injustice worsens. Damming is a common solution to freshwater scarcity, but this very commonly leads to reduced river flows or diversions further downstream, as has been felt around the Tigris river in Basra, the Salween in Myanmar and Thailand, and the Nile in Egypt. Capel Celyn, one of the last remaining Welsh-speaking communities, was deliberately flooded in 1956 to create a reservoir to provide water for Liverpool’s industrial expansion, causing the whole community to lose their homes.

Elsewhere, anthropogenic impacts are not experienced equally: river pollution impacts those downstream far more severely than those doing the actual polluting. In Alberta, Canada, First Nations communities downstream from a huge tar sands extraction project suffer significant exposure to toxins, which threatens their and their livestock’s health, and reduces their ability to hunt and fish.

In many Indigenous populations, water is embedded as more of a member of the community than a commodity, holding its own spirit and knowledge. The right to fish and maintain stewardship of oceans is, in a similar way to land, an integral aspect of sovereignty for many different groups. This includes Indigenous groups such as those around the Northern Bering Sea, and the Bajau Laut people in Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines. Many Indigenous communities are disproportionately impacted by the destruction of water systems and left out of the conversations that influence the poorly thought through activities leading to water insecurity. This includes the Cucapa tribe in Baja, California, Mexico, and Native Hawaiians on the island of O’ahu, where this ecological destruction is simultaneously a cultural one.

In Blue New Deal: Water, Ice, Oceans, a chapter in Perspectives on a Global Green New Deal, Sunil Acharaya shares an example of the Himalayan context:

“Around 1.9 billion people across the South Asian subcontinent depend upon Himalayan Glaciers for drinking water, agriculture and energy…At the current rate of global greenhouse emission and warming, the Himalayas could lose two thirds of its glaciers by 2100. Glacial lake outburst floods will wash away people and infrastructure in the mountain slopes with more frequent floods…In the longer term, we will see persistent droughts with glacier-less mountains and water-less rivers.”

Culture’s role

Thinking about all these entanglements and connected crises, it feels overwhelming to think of ways in which we can begin to respond to them. Creative and cultural responses can help us to deconstruct these issues and think about methods of practising care and community. Innovative projects like Artsadmin’s Museum of Water offer new ways to think about our vastly ranging interactions with the substance. Small Island, Big Song, produced by BaoBao Chen and Tim Cole, unites Indigenous musicians across islands on the Pacific and Indian Oceans to collectively explore their changing environments and ongoing challenges, culminating in two albums, a film and a global concert tour. Toxicity’s Reach by Abandon Normal Devices reaches into increasingly polluted waters and pulls out ways to reimagine and maintain hope.

Further Readings & Resources

Seini F Taumoepeau (CCL Australia) was involved with Restor(y)ing Oceania in Venice.

Julie’s Bicycle – Water Management at Outdoor Events Guide

Julie’s Bicycle – Water Management in Buildings Guide

Surfers Against Sewage – 2023 Water Quality Report

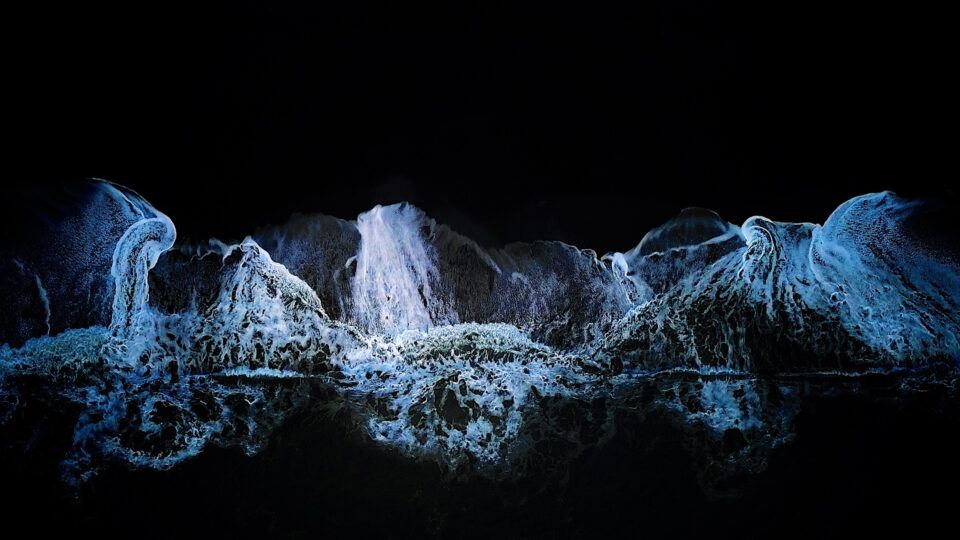

Header image: Adam Sébire / Climate Visuals