- Posted on August 13th, 2020

No Environmentalism in a Silo: What it Means to Talk About Race in our Climate Crisis

– Written by Yingbi Lee, former Communications Coordinator at Julie’s Bicycle

In Singapore, where I grew up and where I’m writing this now, the natural environment feels like something you have to escape from. It’s not hard to imagine why, when the year-long 30°C temperature and humidity get unbearable, and bring the insects out to play. But it’s an even bigger change to get used to after living in South London for four years, where the green spaces dotting every neighbourhood provide a place to escape to, especially when summer comes around. Reconciling this change in my relationship with the environment reminds me of how easy it is to get trapped into thinking of human society and the natural environment as separate from one another, and often as entities that need to be protected from one another in order for either to be preserved. This was discussion that was brought to the forefront of how I approach environmental activism during the production of Judy Ling Wong’s episode of The Colour Green.

No environmentalism in a silo

One of the founders of the Black Environment Network (BEN) in 1987, Judy tells us that early conversations and research the organisation engaged in uncovered a fundamental difference in the way people of colour frame their relationship with the environment, in contrast to the mainstream environmental movement at the time. Environmentalism then was largely concerned with protecting the environment from degrading forces of human activity. Conversely, people of colour tended to speak of how the natural environment can contribute to human wellbeing, such as providing a source of sustenance, or having physically or emotionally healing qualities. As Judy puts it in her podcast episode: “there is no such thing as a purely environmental project”.

Over thirty years on from BEN’s founding, I struggle to see how much has changed from the limited access people of colour have to the mainstream environmental movement that Judy described. From 2017 to 2018, the percentage POC staff in environmental NGOs and foundations in the US fell. The disparity is even starker when it comes to positions of leadership, with senior staff in foundations dropping from 33% to a mere 4%.

Wretched of the Earth

In 2015, the Wretched of the Earth bloc – comprised of indigenous activists from across the world, and black and brown people living in the UK – found their hard-won place at the front of the People’s Climate March in London replaced by people donning animal headgear. Despite growing evidence and recognition that the Global South and people of colour in the Global North are at the frontlines of the climate crisis, their voices continue to be sidelined in favour of prioritising narratives around the protection of biodiversity from environmental degradation and climate change.

But it’s not only about the numbers or a tokenistic inclusion of people of colour in environmental groups. The Green 2.0 working group highlights insular recruiting, alienation and “unconscious bias” as key factors that are limiting the retention of people of colour after the hiring process – which reflects the poor effort on behalf of organisations to reach out and engage with the concerns of the people of colour they allow into their movement. Wretched of the Earth’s open letter to the People’s Climate March shares their struggle securing their rightful place at the front of the march, which appeared contingent on the bloc sanitising their message for the benefit of the egos and emotions of the march’s intended audience. Just months ago, Extinction Rebellion has been criticised by black and brown activists like Black Lives Matter UK for adopting tactics that engage with institutions that have long histories of brutality against people of colour, and adopting rhetoric that ignores the disproportionate impact of climate change on marginalised communities across the world.

Unique challenges in times of crisis

These lacklustre attempts to diversify reflect how people of colour’s inclusion in the mainstream environmental movement is subject to their assimilation into white institutions and the privileged concerns white people have in regards to the environment. It demonstrates an ignorance – deliberate or not – of the unique challenges people of colour and other marginalised communities face in times of climate crisis.

“The agreement it seems was contingent upon us merely acting out our ethnicities – through attire, song and dance, perhaps – to provide a good photo-op, so that you might tick your narrow diversity box. The fact that we spoke for our own cause in our own words resulted in great consternation: you did not think that our decolonial and anti-imperialist message was consistent with the spirit of the march. In order to secure our place at the front, you asked us to dilute our message and make it ‘palatable’.”

When I shared my work on the podcast with a white friend, they asked me why we were highlighting the voices of artists and activists of colour in the UK. They acknowledged that communities in the Global South feel the impacts of climate change sooner and more severely, but wondered: How do the relationships people of colour in the UK have with the environment compare to those of white communities?

Linking up with social justice

While they were speaking from a lack of first-hand understanding of the invisible barriers people of colour face in accessing the natural world, especially rural environments, their question reflects a pretty widespread perception of a clear divide between environmental justice and racial justice within the Global North. In her episode of the podcast, Ama Josephine Budge also touches on feeling a sense of alienation not only as a person of colour in the environmental movement, but also as an environmental activist in the anti-racism activist circles. The lack of racial and ethnic diversity in the mainstream environmental movement has generated a vicious cycle in which the environment is a predominantly white concern that comes secondary to other issues in social justice.

But like Ama, the other guests spoke to Baroness Lola Young about their deeply personal relationships with the environment, in ways that are inextricable from their racial and ethnic identities. For me, Judy’s comment about the different ways in which people of colour framed their relationship with the environment in contrast to the mainstream environmental movement put into context all the other conversations in the podcast series, because this conception of the environment stems from the ways in which communities have been living with the land since prior to European colonisation.

Inspired by Indigenous relationships to the land

What European colonisers perceived as untouched wilderness in the Americas had already been transformed by a long history of Indigenous activity, from agriculture and hunting to building shelters. Ignoring this history of interaction Indigenous people have had with the land, Western narratives of environmental protection cast the environment as a passive object lacking agency, rather than something that we are constantly living in. Ironically, Indigenous communities have proven stewards of the environment – a vast majority of the planet’s biodiversity can be found on Indigenous lands, despite covering only 22% of the Earth’s surface. The 2018 IPCC report cites traditional ecological knowledge as critical for adapting to environmental changes.

Developed over many generations, Indigenous communities’ methods of living with the land foregrounds the importance of developing local, grassroots solutions for mitigating or adapting to climate change. Approaching the environment as something that contributes positively to human life and wellness is useful to understand not only as something that has been limiting POC access to the mainstream environmental movement, but also as a perspective that can constructively help us live in the environment in a way that is truly sustainable.

“We live in a culture where we’re waiting for a hero and want to blame a scapegoat…There ain’t no hero and there ain’t no scapegoat… It’s all of us and we’re all in it together… if you’re waiting for some saviour or hero, it’s too late. If you blame it all on the scapegoat you’re not taking responsibility.”

– Kareem Dayes, from The Colour Green podcast

A sense of reconnecting

To disconnect the environmental movement from conversations surrounding race and ethnicity is to ignore how the impact of climate change is stratified across levels of urban development across the globe, and across racial lines within countries. It ignores the Western and colonial notions of nature and ecology that underpin the unfettered expansion of capital and consumption that drives environmental degradation. It devalues the relationship communities of colour have with the environment, and strategies for adapting to environmental changes that Indigenous communities have spent centuries developing.

Bearing Judy’s words in mind, I’ve started seeking new ways of reconnecting with the environment that I’ve spent a long time trying to avoid – even if that only means taking a fifteen minute break from my work to find some comfort in the heat and humidity of the air outside, or to appreciate that many of the insects that I might consider a nuisance are more prolific pollinators than bees and are integral elements of the urban ecosystem.

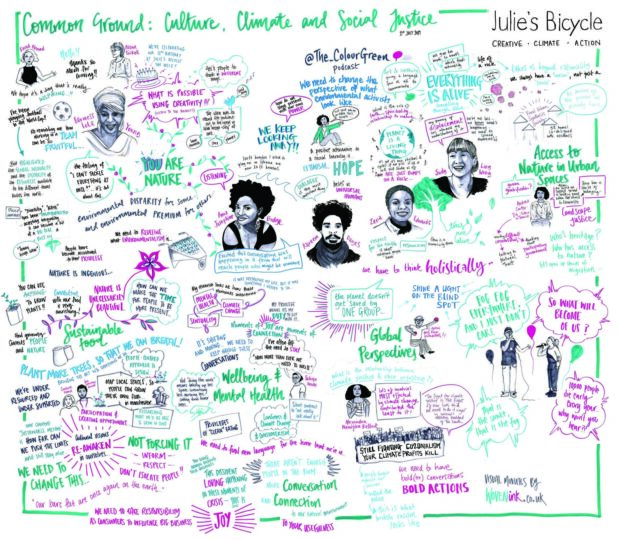

There’s so much more to this conversation than can be contained in a single blog post, or even within a few episodes of a podcast, but I hope that they open up several new dimensions to the discussion around environmental and social justice. The lack of visibility of activists in this space does not speak to the lack of thought, effort, and action that they’ve been engaging in for decades. Below, I’ve linked articles, reports and organisations that delve deeper into the issues I’ve touched on here. As part of the launch of The Colour Green podcasts on July 1st, I’ll be taking over @The_ColourGreen on Twitter on the week beginning on July 15th, and I’m looking forward to continuing the conversation there.

Resources:

-

- “Open Letter from the Wretched of the Earth bloc to the organisers of the People’s Climate March of Justice and Jobs” | Reclaim The Power

- “Are Extinction Rebellion whitewashing climate justice?” by Leah Cowan | gal-dem

- “’A lot at stake’: indigenous and minorities sidelined on climate change fight” by Emily Holden | The Guardian

- “To share or not to share?: Tribes risk exploitation when sharing climate change solutions” by Paola Rosa-Aquino | Grist

- “How Green Groups Became So White and What to Do About It” by Diane Toomey | Yale Environment 360

- “The State of Diversity in Environmental Organizations: Mainstream NGOs, Foundations & Government Agencies” Report | Green 2.0

- “GoGreen19: Climate change is a racist Issue” by Zamzam Ibrahim & Laura Clayson | People & Planet

- “Environmental Ethics in a Post-Natural World” by Steven Vogel | UTNE Reader

- The Black Environment Network

- Indigenous Environmental Network

- Global Grassroots Justice Alliance

- Climate Justice Alliance